Spring 1999 Santa Rosa Press

Democrat Editorials on Reproduced with permission Monday, February 22, 1999 Editorial Waterfall park

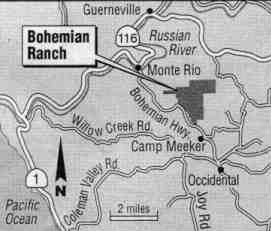

We'll learn more on Tuesday as the board measures prospects for what could be a showplace of a regional park in the west county. After eight years of experience, the political and institutional resistance to using open space tax revenues for parks and trails is well-documented. A new summary shows the district has engaged in transactions involving 25,743 acres -- and exactly 48 acres are connected to a regional park. By comparison, development easements on privately held agricultural lands total 19,753 acres, and easements on privately-held, forever-wild lands total 5,354 acres. Now comes the opportunity for the district to participate in the acquisition of a prime site for a regional park. The 960-acre parcel, east of Bohemian Highway between Camp Meeker and Monte Rio, features redwoods, trails, habitat for endangered plants, four creeks, and a 30-foot waterfall. Locals know it as "waterfall park." Plenty of obstacles remain. The county parks deparment must accept responsibility for owning and maintaining the park, which means that supervisors must make a financial commitment. Nearby residents are pledging to raise money to help witha variety of fundraisers, including a Luther Burbank Center for the Arts concert headlined by rockers Mickey Hart and Sammy Hagar. They ought to be held to their commitment as one very tangible measure of a community's support. And money is always an issue. At the end, the appraised value has to make sense from a public benefit standpoint. But it can't happen at all without the participation of the Open Space District. Groups opposed to public recreation projects argue -- correctly -- that more money is required to purchase property outright than is needed to acquire a development easement on private property. In other words, the more money spent on parks, the less money available for farmland purchases. But after eight years in which regional park acquisitions only 0.19 percent -- less than 1/500th -- of the total, one would hope these groups could loosen up. We're talking, after all, about a wildlands park that could inspire visitors for the next 1,000 years -- and then some. We're talking about a community that is willing to put its money where its dreams are. As a practical matter, the district is not going to be overwhelmed with park acquisition requests because state and local governments don't have the money to manage a bunch of new parks. As a political matter, the influentials in orbit around the Open Space District should know the public expects a whole range of benefits from the open space tax -- not only large payments to large landowners whose property will remain closed to the public. This debate emerges as the Open Space District is in the midst of fundamental changes. A new general manager is being recruited. It's likely the Board of Supervisors will re-organize the agency -- streamlining the acquisition procedure, simplifying an unnecessarily convoluted governing structure, creating a more direct line of accountability to the board itself. It's the perfect time to acknowledge that the district has a role in public recreation -- and to spell out the parameters of future projects.

Friday, February 26, 1999 Editorial Nine years later In Sonoma County, the public commitment to open space preservation remains strong. What isn't so secure is public confidence in the way open space monies are spent. Since the open space tax was approved by voters in 1990, the Open Space District has had its good days and its bad days. More than 25,000 acres of farm and wild-land areas have been permanently protected through the purchase of development easements, including parcels that provide permanent open space between cities. But purchases in remote areas and the resistance to public recreation projects caused controversy. Critics wanted to know: Why is so much money being spent on far-flung properties that are not subject to development pressures? Why isn't a portion of the money being used to buy parks and trail easements? The cumbersome and convoluted system for governing the district -- which includes an advisory committee, the Open Space Authority and the Board of Supervisors -- inevitably creates confusion and uncertainty about who is in charge. The arrangement makes the process less accessible to the public, creating the impression that the district is being maintained as a private sandbox for a handful of influential groups. This perception was reaffirmed when the district announced plans, later scotched by the Board of Supervisors, to spend tax funds on a lavish party. In public relations, the district often proved that it was less than gifted. This week, the Board of Supervisors signaled its intention to place a tighter rein on the district, taking back authority over acquisition priorities. This is a welcome change, even if it should have happened a long time ago. After nine years, it's inexcusable that the district is still scrambling to to put in place an efficient management team -- and goals and policies that everyone understands. Time flies, whether you're having fun or not. The current quarter-cent sales tax is approaching the halfway point of its existence. In 2010, voters must be asked to renew the tax. In some ways, that's a long time from now. But government works slowly, especially in the business of protecting open space. Every transaction is complicated and unique. Moreover, it's unlikely that cynicism toward government and taxes will decline in the next decade. Thus, the burden is on the Board of Supervisors to build a record of accomplishments that will pass the test of public scrutiny. The job starts now. Tuesday, March 9, 1999 Editorial Special report A consultant would charge tens of thousands of dollars for the information delivered to the Board of Supervisors this week for the price of a couple of newspapers. In a special report, published on Sunday and Monday, Staff Writer Tom Chorneau provides a valuable baseline for measuring the performance of the Sonoma County Open Space District. The achievement of the first eight years -- more than 26,000 acres protected from development -- affirm the voters' 1990 decision to adopt a quarter-cent sales tax to preserve farmlands and natural areas. The first county in the nation to adopt such a tax now ranks third in the nation in land conservation. At the same time, too many decisions have left the impression that the district lacks a clear understanding of its mission.

As the Board of Supervisors selects a new management team and imposes new acquisition priorities, these deficiences can be repaired. Acquisitions that discourage sprawl ought to come first. The acquisition list ought to make room for parks and trails that the public can use. Finally, uniform appraisal standards and conflict-of-interest rules would reassure the public that district monies are being used to maximum effect. With these initiatives, public confidence in the district will match the public's commitment to the goal of protecting this county's resources and unique landscape. Sunday, April 4, 1999 Editorial Notebook More people, more parks Pete Golis It's Sunday morning, and the Spring Lake loop is alive with people -- walkers, joggers, cyclists, kids in strollers. The lake is dotter with fishermen's tiny boats; along the banks, youngsters cast lines from shore. Past the swimming lagoon, a few hikers turn away from the lake, following one of several trails into Annadel State Park. Once there, they can walk dozens of miles of trails through meadows and woodlands with sweeping views of the surrounding valleys. If the hikers choose, they can trek all the way to Kenwood, a straight-line distance of more than seven miles. Back at Spring Lake, other visitors follow the loop to the west side fo the lake, returning to nearby Lake Ralphine, Howarth Park and the neighborhoods beyond. This is, safe to say, an incredible community resource. On this sunny, spring day, people are hiere for exercise and inspiration, for bird watching and fishing, for solitude and conversation, for picnicking and boating. In a few weeks, they will be here for swimming, too. To calculate the worth of these parks, it's necessary to gather all the pleasures of this Sunday morning and multiply by . . . forever. This complex was an earlier generation's gift to posterity. In the 1960s, the city created Howarth Park. In the 1970s, the county developed Spring Lake County Park. Also in the 1970s, a group of community leaders (led by businessman Henry Trione) decided 5,000 acres of grassland and woodland would make a better state park than a subdivision. Good choice. We call it Annadel State Park. Since 1975, the population of Sonoma County has increased from 245,000 to 450,000 people, but in several important ways, we haven't kept pace with the demand for outdoor recreation. Except in Rohnert Park, playing fields are scarce, not to mention poorly maintained. Several areas of the county, notably the south county, lack a [sic] large, regional parks. The demand -- and need -- for more wild land parks and trails continues to expand. Some days, Annadel and environs can be too alive with people. Money is the biggest problem. Federal and state governments don't provide the large block grants they once did. Since Proposition 13, cities and counties don't have as many resources to apply to the acquisition, development and management of parks. A major athletic field complex on West Third Street in Santa Rosa is, at last, ready to go -- as soon as the city can find $8 million. Big and small benefactors are being sought. For a gift, the city will put your name on a tree, a bench, a square foot of pavement. This is not begging, but it comes close. Since Proposition 13, most new parks have been financed by developers' fees, which means, by and large, that they are small, neighborhood parks. Money is not the only obstacle, however. Neighborhood politics and the glacial pace of bureaucracies make everything more difficult. It took two years for the neighborhood to agree to concessions for the West Third Street site, which is little more than green grass, bathrooms and a parking lot. Plans for playing fields on Old Redwood Highway, across from Cardinal Newman High School, are still caught up in red tape. Petalumans became bitterly divided over the choice between a regional park and a nature preserve when they should have been trying to do both. After the open space district acquired public access to McCormick Ranch in 1995, people were promised opportunities to hike the headwaters of Santa Rosa Creek, but the gate remains locked and the signs [sic] says, "Private Property, no tresspassing." Meanwhile, key players at the open space district continue to resist public pressure to make a larger share of its resources available for public recreation. One early opportunity: The proposed, 1,000-acre Bohemia Ranch Waterfall Park in the redwoods between Monte Rio and Occidental. What to do? Private fund-raising becomes increasingly important. A big boost for Bohemia Ranch Waterfall Park, for example, is expected from a benefit rock concert later this month. Vice President Al Gore's new environmental plan proposes a few bucks for park acquisitions. In November 2000, Californians are likely to vote on a park bond measure that provides some -- underline some -- help for local agencies, as well. A city truly committed to supporting parks could enact a parcel tax -- but most elected officials will run for cover. Most of all, whether Sonoma County gets the parks it needs will depend on citizens' willingness to apply their energies to the task. It's going to take a big push to move beyond the impasses. Civilization is defined by its public places, whether a downtown plaza, a regional park or a natural landscape. Think of Healdsburg Plaza or Ragle Ranch Park in Sebastopol or the marvelous string of state beaches along the Sonoma County coast. The question waiting to be answered is: What kind of public recreation will this generation of Sonoma County Residents provide to posterity?

Thursday, April 8, 1999 Editorial No trespassing The 171-acres Skiles ranch adjacent to Jack London State Park fits the criteria for public access. The property, studded with oak, pine and fir, would be a natural link in a long-sought ridge trail on Sonoma Mountain. But the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors voted this week to give the land owner $632,000 without receiving a public access component in return. Supervisors defended the decision by saying that a public trail might be negotiated later. But the landowner, having collected $632,000, no longer has an incentive to negotiate. With this deal, supervisors pushed this property off the agenda and gave away their leverage. What the county receives for $632,000 is the landowner's promise not to build a second or third home on 171 acres. For the growing number of people who wonder why a few dollars of open space district funds aren't being spent on trails and other public recreation opportunities, this is not a decision that demonstrates the district's promise to do better. Open space district officials, it seems, continue to lack the energy necessary to press the issue with potential sellers. Part of the problem is that the public access issue has become radioactive from a political standpoint. The bitterness that grew out of the Lafferty Ranch controversy in Petaluma is now poisoning the environment for cooperation all over the county. As of now, property owners who might be open to an access agreement now fear criticism from neighbors who oppose access. With this decision, supervisors make clear they don't want to deal with the political controversies associated with public access. They choose to deal instead with the growing suspicion that every effort is being made to prevent open space district tax revenues from being spent on public recreation. Thursday, April 29, 1999 Editorial No deal The facts behind the demise of a $2.5 million sale of the pristine Bohemia Ranch to an Occidental logger may never be known. Did public outrage frustrate Chuck Butler's attempt to find financial backing? Were potential investors unwilling to run the inevitable gantlet of opposition that would confront any logging efforts? Or was this just an orchestrated attempt at speeding up a purchase by the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District and driving up the cost? Regardless, the failure of the deal was enough to generate a roar of approval at Luther Burbank Center on Tuesday when Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart reported during a benefit concert that Butler had not made his 5 p.m. deadline for coming up with the money. It would be hard to believe most in the county didn't have the same response to the news. This opens a door for the Open Space District to renew negotiations for adding the 960-acre ranch -- also known as Waterfall Park -- to its inventory of publicly held properties. Given the events of the past two weeks, the public is not likely to tolerate any more delays in completing this deal, which has been years in the making. But that does not mean there are not obstacles. The main stumbling block, it appears, is the difference of some $100,000. Sonoma county supervisors contend, by law, they are prohibited from paying more than $2.4 million, the appraised value of the property. The owner, Oregon-based Norman McDougal, has said he wants nothing less than $2.5 million, the same price offered Butler. The funds raised at Tuesday's Open Nature benefit concert, an estimated $150,000, may help close this gap. Another option may be to lower the sales price by allowing McDougal to retain a homesite on the property. Either way, a special meeting of the Open Space Authority will be held this morning, and members should be encouraged to wrap this up quickly. Sonoma County has been shown something worth preserving -- a park offering natural beauty, tranquility and accessibility. The Open Space District has been given something it can't afford to blow -- a second chance. |

Does the Sonoma County

Board of Supervisors believe the Open Space District has

a role in public recreation?

Does the Sonoma County

Board of Supervisors believe the Open Space District has

a role in public recreation?